Entitlement: The Parenting Fear We’ve Got Backwards

There are so many labels for parenting now that it can feel like we spend more time debating terminology than actually parenting.

Gentle. Respectful. Conscious. Calm. Authoritative. Attachment-based. Depending on where you’re standing, people will argue passionately about what each one really means.

But beneath the semantics, most of these approaches are aiming for essentially the same thing.

They are all trying to answer a very human question: how do we raise emotionally healthy, resilient children who can recognise their own feelings and needs, while also learning that other people have feelings, needs, and limits too. Children who grow up with empathy, responsibility, and an understanding of accountability, not because they were controlled or indulged, but because those capacities were learned through secure relationships.

Across the many labels for modern parenting, one criticism reliably appears: that this is why children today are entitled.

Children are seen as demanding, fragile, or unable to tolerate frustration. Emotional attunement is considered an indulgence and respect is mistaken for a lack of boundaries and leadership.

Often I hear, “The world is not going to care what they are feeling!” Children, it is argued, need to toughen up early if they are going to cope later.

The problem with this argument is that it misunderstands how resilience actually develops. Learning to name and regulate emotions in the context of safe relationships does not make children less capable in the world. It is precisely what allows them to tolerate frustration, adapt to challenge, and function well in environments that are not emotionally accommodating.

The Fear of Entitlement Makes sense

Many adults were raised with the idea that firmness and emotional restraint were what kept children grounded, grateful, and socially aware. In that context, warmth and responsiveness can look like indulgence. Respect can be mistaken for letting children run the show.

But that assumption rests on a misunderstanding of what creates entitlement in the first place.

What do we actually mean by “entitlement”?

Part of the confusion in this conversation is that entitlement itself is rarely defined.

In psychological research, entitlement does not mean a child who has needs, emotions, or strong preferences. It refers to a stable pattern of expecting special treatment without regard for others, coupled with low empathy and low responsibility for impact.

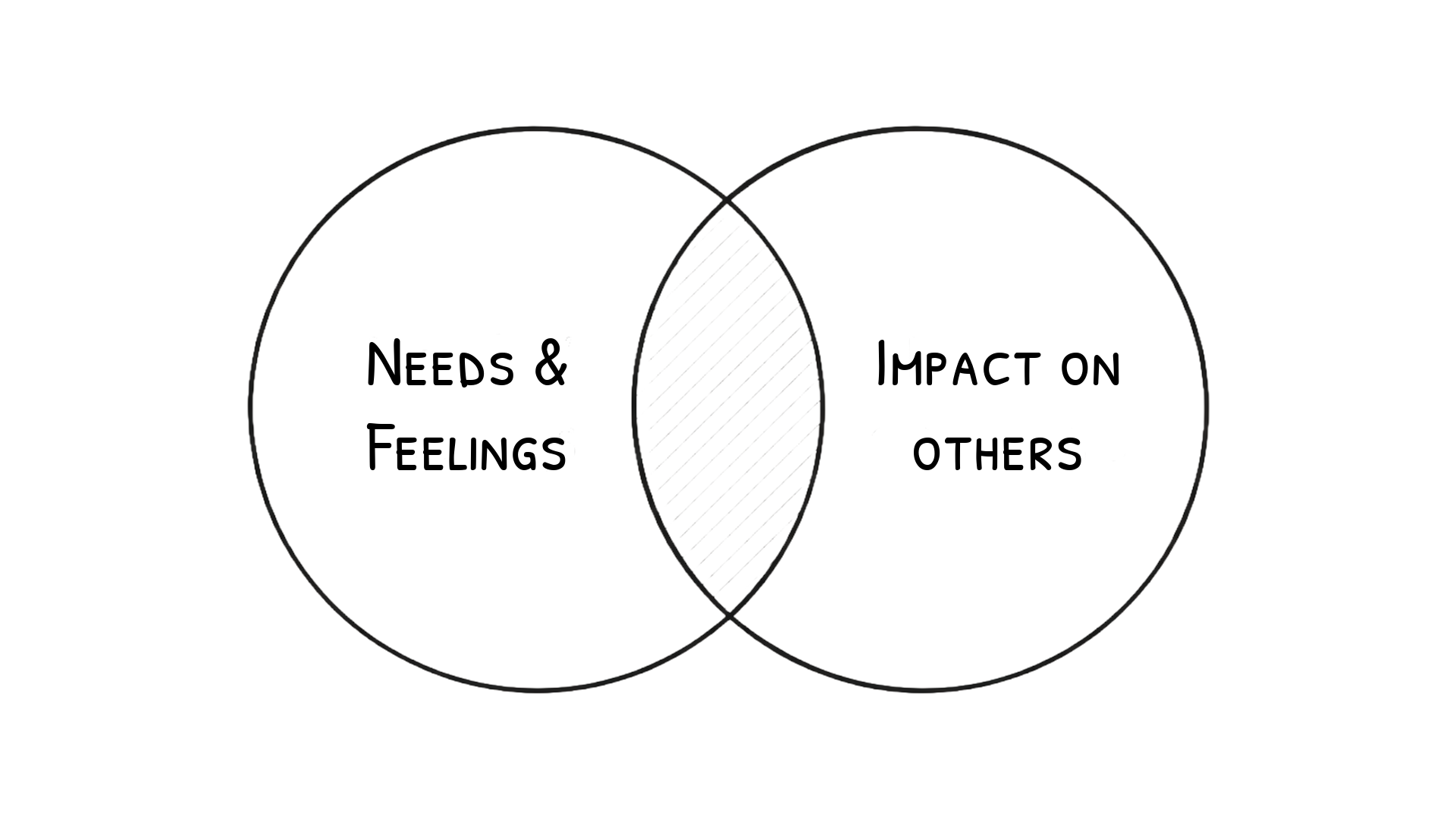

In other words, entitlement is not about having feelings. It is about struggling to recognise that other people have feelings, needs, and limits too.

This matters because when parents worry that emotional attunement creates entitlement, they are often responding to a caricature. A child who can name their feelings, ask for help, or express frustration is not displaying entitlement. Those are signs of emotional awareness and intelligence.

True entitlement develops when children are not supported in learning perspective, accountability, and relational impact. And those capacities are not built through emotional dismissal or rigid control. They are built through repeated experiences of being emotionally met while also being guided to consider those around them.

When we define entitlement this way, it helps to bring clarity to the discussion. So that the issue is no longer whether children’s emotions are respected, but whether they are helped to grow into awareness of the wider world.

What the research actually shows

Decades of developmental research consistently point to a style of parenting associated with the lowest levels of entitlement and the highest levels of responsibility, empathy, and self-regulation. This is what psychologist Diana Baumrind described as authoritative parenting.

Authoritative parenting is not permissive. It combines emotional attunement with clear expectations, boundaries, and adult leadership. Children are taken seriously as human beings, but are not placed in charge.

Research following this model shows that children raised with authoritative parenting are more likely to:

take responsibility for their behaviour

consider the impact of their actions on others

tolerate frustration

show empathy and cooperation

In other words, respect does not produce entitlement. It supports the development of internal regulation and social responsibility.

Why respect builds accountability, not entitlement

From a neuroscience perspective, children develop empathy and self-control through repeated experiences of being emotionally met and observing limits. When a child’s feelings are acknowledged but not allowed to override others, the brain learns something crucial: my inner world matters, and so does yours.

Research shows that healthy motivation and responsibility grow when children experience:

connection

autonomy within boundaries

clear structure

Entitlement is more likely to develop when children are either indulged without limits or controlled without understanding. In both cases, they miss the chance to develop an internal sense of responsibility and consideration for others.

Respect is not indulgence

Parenting with respect still includes frustration, limits, and disappointment. Children are not protected from reality; they are supported through it.

What changes is not whether boundaries exist, but how they are held. Respectful, relationship-based parenting teaches children that emotions can be expressed, needs can be named, and that limits are real. It teaches them that relationships involve consultation and negotiation, accountability, and repair.

That is not a recipe for entitlement; it is a foundation for social competence.

The long view

Children who are raised this way do not grow up expecting special treatment. They grow up expecting relationships to include empathy, limits, and mutual consideration.

So the fear that respectful parenting leads to entitlement is understandable, but it is not supported by evidence.

What this approach actually builds is capacity in crucial areas: emotional regulation, personal responsibility, and living well with others.

And that is the opposite of entitlement.